Depression is predicted to become one of the leading causes of premature mortality and ill-health in the next 20 years. To prevent this happening, we must understand how depression develops throughout people’s lives. Looking at symptoms of depression early in childhood and adolescence is important as 75% of those with a mental health condition start developing it before the age of 18.

There are several questions that come to mind when thinking about symptoms of depression throughout development. What proportion of children and adolescents has depressive symptoms? Do symptoms of depression usually increase or decrease throughout adolescence? For those with symptoms of depression, are they usually mild or extreme?

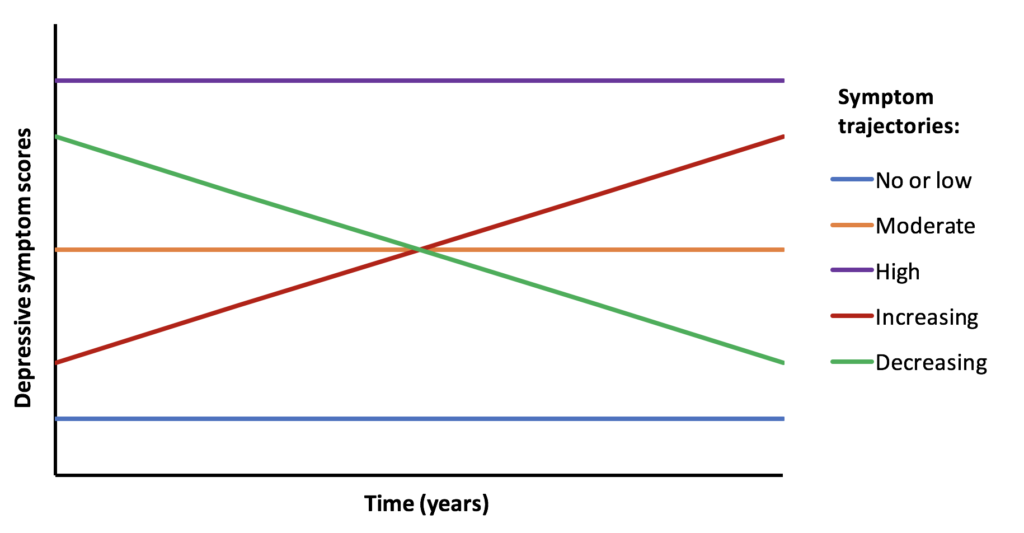

A recent systematic review by Shore and colleagues (2017) explored whether there is evidence for different patterns in the development of depressive symptoms throughout childhood and adolescence. These observable patterns, called depressive symptom trajectories, may show stability, increases or decreases in symptom severity over time.

How do depressive symptoms usually change throughout childhood and adolescence?

Methods

In this paper, a trajectory describes the course of depressive symptoms over time. People are likely to have different trajectories of depressive symptoms. Researchers have recently developed ways to model these trajectories using data from longitudinal studies. This approach assumes that the population is composed of distinct groups of people, each with a different underlying trajectory of depressive symptoms.

Trajectory modelling identifies groups of individuals with similar progressions of depressive symptoms over time. It can also be used to identify factors that influence which trajectory each individual is in. This means we could identify factors linked to persistent (vs decreasing) depressive symptoms. I’m not going to talk about this in any more detail, but if you’re interested you can find out more about Trajectory Analysis on the Columbia University website.

Physicists can model the trajectory of a satellite, and now it seems, medical researchers can model the trajectory of depressive symptoms.

Shore and colleagues (2017) present a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies modelling the trajectories of depressive symptoms in children and adolescents. They searched EBSCOHOST, Google Scholar and Scopus databases for peer reviewed articles using the terms adolescent, depression and trajectory.

The inclusion criteria were:

- Longitudinal studies

- Baseline data collected when participants were less than 19 years old

- Non-clinical samples

- Data analysed for trajectories of depressive symptoms

One author performed the database search and reviewed studies, with the final studies reviewed by a second author. Research quality was assessed and a risk of bias analysis was performed, but not reported. As previous research used different measures of depression, the authors had to convert depressive symptom scores. The most common measure was used for this (the Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale (CES-D)) with cut-offs for low, moderate and high depressive symptom severity.

Shore and colleagues used a random-effects meta-analysis to determine whether there was evidence for different depressive symptom trajectories across previous studies. They estimated the prevalence of these trajectories, weighted by the samples sizes of each study. Random pooled effects estimates averaged across studies to determine the effect size for each trajectory. They also assessed factors included in 2 or more studies which might differentiate high and increasing from low trajectories of depressive symptoms.

Results

This review included 20 studies published between 2002 and 2015. These studies found evidence for between 3 and 11 trajectory groups. The authors recalibrated the groups in previous studies to fit into the five depressive symptom trajectories shown in Figure 1 below: no or low, moderate, high, increasing, or decreasing depressive symptoms.

Figure 1: A basic illustration of the five most common depressive symptom trajectories in previous research.

As shown in the table below, the no or low depressive symptom trajectory was by far the most common, with 56% of the children and adolescents sampled estimated to be in this group. Those with moderate sustained depressive symptoms were the next biggest group. The smallest groups of children and adolescents were those with high, increasing, and decreasing depressive symptom trajectories.

- There was evidence for some predictors of the worse trajectories. Gender was the most frequent risk factor, with females experiencing higher and more persistent depressive symptoms than males

- Other risk factors for high or increasing trajectories were socioeconomic status, stressful life events, conduct issues and substance misuse

- Protective factors associated with reduced risk of high or increasing depressive symptom trajectories were strong parental relationships and peer support.

| Depressive symptom trajectory | Weighted prevalence estimate | Random pooled effect estimate |

| No or low | 67% | 56% |

| Moderate | 17% | 26% |

| High | 3% | 12% |

| Increasing | 4% | |

| Decreasing | 8% |

Strengths and limitations

This is the first meta-analysis of trajectories of depressive symptoms in children and adolescents. It provides a good summary of previous evidence and demonstrates that there are several different trajectories of depressive symptoms throughout adolescence.

However, all included studies found evidence for several trajectories. Studies that found no evidence for multiple trajectories may not have been published, so this review may be influenced by publication bias. The scope of this review was also limited. The authors found no evidence for differences in trajectories between studies starting before vs after puberty. This could be because there were so few studies that started early in childhood.

Additionally, a test of heterogeneity showed significant variation in trajectory prevalence estimates across studies. Individual studies identified between 3 and 11 different trajectories. This could be due to the differences in assessment, response categories or analyses. Although depressive symptom scores were recalibrated, the heterogeneity makes these findings less reliable.

A final limitation of this review is that it is unclear why the authors chose to use 5 trajectory groups. There are other alternative trajectories, such as episodic symptoms, which have not been included. I spoke to the authors about this, who told me they did not decide on the number of trajectories beforehand but chose the most common groups from the research reviewed. It would be interesting to hear a summary of this process given the variation in the number of trajectories identified in previous studies.

Conclusions and implications

This review shows clear differences in the way depressive symptoms develop during adolescence. Most children and adolescents have no or low depressive symptoms throughout development. A small proportion of children and adolescents experience high or increasing depressive symptom trajectories.

Identifying differences in the development of depressive symptoms has implications in four main areas:

- Understanding how individuals with early elevated symptoms will recover

- Developing diagnostic categories of depression for children and adolescents. If there are robust differences in symptom trajectories, these may constitute different diagnostic subtypes of depression. New taxonomies could enable more reliable assessments and interventions

- Designing and implementing targeted therapeutic interventions and prevention strategies. It is important to target those on the high and increasing depressive symptom trajectories. New targeted prevention strategies are needed as a recent Cochrane review found insufficient evidence to implement depression prevention programmes for children and adolescents

- Identifying predictors of the different trajectories. This review provides support for the importance of gender, socioeconomic status, stressful life events, conduct issues, substance use, parental relationships and peer support in the development of depressive symptoms. These could be targets for interventions. They also enable us to identify who is at most risk of being on high or increasing depressive symptom trajectories, for example girls or those who have experienced stressful live events.

This review is a good starting point for understanding child and adolescent depressive symptom trajectories. Further research is needed, using consistent measures and analyses, to provide more accurate estimates of the prevalence of different trajectories. In addition to developing intervention and prevention strategies, future research could also assess the association of each trajectory with adult mental health problems.

Risk factors for depression included being female, socioeconomic status, stressful life events, conduct issues, substance use, and problems with parents and peers.

Links

Primary paper

Shore L, Toumbourou JW, Lewis AJ, Kremer P. (2017) Longitudinal trajectories of child and adolescent depressive symptoms and their predictors: a systematic review and meta‐analysis (PDF). Child and Adolescent Mental Health doi:10.1111/camh.12220.