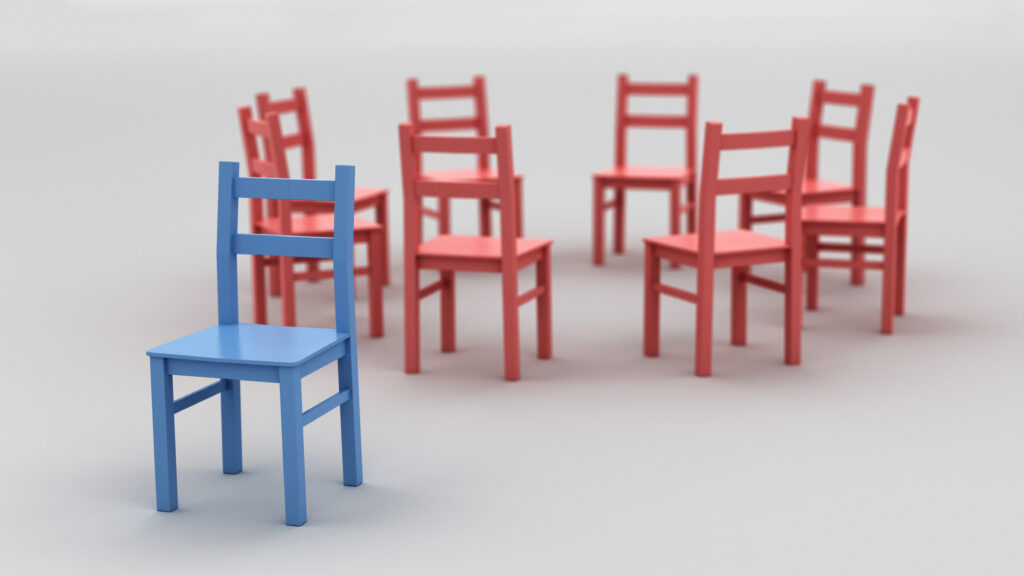

Transport yourself back to school. Were you ever told that you couldn’t sit with the popular group? Did this make you feel ignored, undesired, or neglected? Now imagine if the whole of society didn’t want you at their table and you had no access to its rights or privileges? This is the reality for up to 14 million people in the UK who are at risk of social exclusion (Office for National Statistics, 2013) and consequently are not accepted by ‘mainstream’ society.

Social exclusion affects vulnerable groups such as people experiencing homelessness, prisoners, sex workers, and people with substance use disorders, and is a key contributing factor to poor physical and mental health (van Bergen APL. et al, 2019). Shockingly, excluded populations are ten times more likely to die early than non-excluded populations (Aldridge RW. et al., 2018).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, over 70,000 households in the UK were made homeless (Jayanetti, 2021) suggesting that the risk of social exclusion and subsequent poor health outcomes is elevated. Therefore, it is of great importance that healthcare professionals understand social exclusion.

Currently, there is no consensus regarding the definition or mechanisms underlying social exclusion. Thus, O’Donnell and colleagues (2021) conducted a qualitative study by interviewing experts in the field and socially excluded individuals.

Social exclusion may affect up to 14 million individuals in the UK.

Methods

In this Irish qualitative study, researchers used maximum variation sampling to select participants, through which they attempted to collect data from the broadest possible range of stakeholders associated with social exclusion. Researchers found potential participants through a network of healthcare professionals and experts working on social exclusion and gatekeepers of appropriate civil society organisations (CSOs).

The authors then conducted semi-structured interviews using a topic guide based on previous research to collect data. After 24 interviews theoretical data saturation was achieved. Participants came from various social exclusion backgrounds, some identifying with two stakeholder categories. These included individuals from CSOs, philanthropic organisations, experts by experience (EBE), service providers, policymakers, and academics. The EBE participants included people experiencing homelessness, people with addiction problems, sex workers, the formerly imprisoned, and members of the Irish Traveller population. Researchers analysed data using thematic analysis.

Results

Defining social exclusion

Participants noted difficulties in concisely defining the concept due to its complex and multidimensional nature. One participant described the concept as “fluid” and changing in meaning depending on who is using the term. Various participants described social exclusion as a lack of “basic” resources, such as education, housing, and healthcare. Other participants cited a lack of income and material resources as most important. Many participants blamed societal structures for permitting people to become easily excluded but making it difficult to re-join society.

Opportunities

Opportunities are the basic needs that must be met to begin to leave exclusion. Participants identified five opportunities that they believed the State should be responsible for ensuring, including finance, education, housing, employment and healthcare. Excluded groups often face difficulties taking advantage of opportunities freely provided by the State, while they also have elevated needs across most of the domains.

Influencing factors

Influencing factors could affect whether a socially excluded person can use available opportunities to begin to leave exclusion. Participants identified four types:

- Intergenerational adverse life circumstances

- Perceived degree of agency or positive control over one’s life

- Significant adverse events, such as being imprisoned, addiction or begging on the streets

- How strongly a person identifies with the excluded group.

Social outcomes

Social outcomes represent the desired results of leaving exclusion and were discussed by participants as the ability to effectively take care of oneself, for example “getting a meal on the table”. Another important outcome is acceptance from the wider society. However, acceptance was viewed as a major obstacle to participation in society, with many participants reporting that acceptance from the ‘mainstream’ could mean losing the support from the excluded community they were a part of. Therefore, people beginning to leave social exclusion could experience “social limbo”.

The end goal for a person leaving exclusion was identified as social participation, for example by “having the ability… to express your voice…”. However, other participants recognised that some people leaving exclusion have “no desire to have full participation in society and live perfectly good lives”.

Influencing factors, such as intergenerational trauma, perceived agency, and adverse events may affect the ability to leave social exclusion.

Conclusions

Researchers defined social exclusion as “the experience of lack of opportunity, or the inability to make use of available opportunities, thereby preventing full participation in society” and developed a novel conceptual model of social exclusion.

Researchers defined social exclusion as “the experience of lack of opportunity, or the inability to make use of available opportunities, thereby preventing full participation in society”.

Strengths and limitations

The study has a representative sample, including not only experts in the field but experts by experience (EBE). The aim was to capture the understanding of the concept, so it was beneficial to include the voices and lived experiences of those affected by social exclusion. The use of maximum variation sampling was beneficial as it allowed researchers to meticulously choose as many possible different types of stakeholders associated with exclusion as participants. Thus, researchers were able to construct a holistic understanding of the concept (Suri, 2011). Yielding reliable and valid data is an important indicator of high-quality qualitative research. The authors ensured this by using respondent validation, whereby participants checked their data for accuracy (Birt et al, 2016). Moreover, the topic guide was included in the appendices, and upon inspection, no questions were leading.

Researchers claimed that a key strength was that the lead researcher already knew some participants and so understood important context prior. However, it is unclear whether the lead researcher also conducted interviews. While it is true that rapport-building leads to richer data (Miller, 2017), this prior familiarity could have encouraged participant bias. For example, social desirability bias, where participants respond based on what they think will ensure they are liked or accepted by the interviewer (Bergen, 2020). Another weakness was that researchers omitted information regarding which specific organisations or excluded groups participants belonged to. It was also not clear whether the EBE group were still considered to be excluded or had left exclusion. These would have potentially been useful grouping tools, as themes could have been compared between specific participant profiles. Furthermore, as this study was conducted with all Irish participants, results may only be generalisable to the Irish population.

The findings of this study may only be generalisable to the Irish population.

Implications for practice

This study has formulated a working definition and novel conceptual framework of social exclusion derived from the knowledge of experts in the field and experts by experience (EBE). As one consistent definition of social exclusion did not exist in literature or practice prior to this study, these findings are greatly beneficial and have implications for both practice and policy.

The existence of a working definition of social exclusion opens doors of education for clinicians. As primary care is an important first step in patients’ healthcare journeys, clinicians must understand the concept to identify and routinely measure the social exclusion status of patients. Therefore, primary health services could be used to identify social exclusion early, which would be effective for signposting patients to the right services.

The current policy aims to decrease levels of social exclusion focusing mainly on the Opportunities level. While work at this level is important, the conceptual framework developed in this study notes the equal importance of Influencing Factors. Therefore, an implication for policy is to support initiatives that would help to disrupt intergenerational vulnerabilities, help those with adverse life experiences to assimilate, and help educate wider society about the concept and how damaging stigma can be.

In conjunction with the working definition, the novel conceptual framework for social exclusion allows for an enriched understanding of the concept and has implications for future research. Forthcoming studies should focus on those who consider themselves to have been successful at leaving social exclusion to gain a better understanding of the process of leaving exclusion and how this is possible. Furthermore, replications of the present study should use more diverse participant samples for results to be generalisable to a larger population.

As a long-time volunteer distributing meals to people experiencing homelessness, I have listened to first-hand accounts of what it feels like to be socially excluded. This group often feels invisible and forgotten by a society that walks on by without giving them a second glance. Something as simple as the human connection of eye contact is impactful for them. Let’s invite more people to the table to sit with us.

Primary healthcare clinicians should educate themselves on social exclusion to identify cases early and signpost appropriately.

Statements of interest

None.

Links

Primary paper

O’Donnell P, Moran L, Geelen S. et al (2021) “There is people like us and there is people like them, and we are not like them.” Understanding social exclusion- a qualitative study. PLos ONE 2021 16(6), 1-19.

Other references

Aldridge RW, Story A, Hwang SW. et al (2018). Morbidity and mortality in homeless individuals, prisoners, sex workers, and individuals with substance use disorders in high-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet 2018 391(10117), 241-250.

Bergen N, Labonté R. (2020). “Everything is perfect, and we have no problems”: Detecting and limiting social desirability bias in qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research 2020 30(5), 783-792.

Birt L, Scott S, Cavers D. et al (2016). Member checking: A tool to enhance trustworthiness or merely a nod to validation? Qualitative Health Research 2016 26(13), 1802-1811.

Jayanetti C. (2021). 70,000 households in UK made homeless during pandemic. The Guardian, 9 Jan 2021.

Miller T. (2017) Telling the difficult things: Creating spaces for disclosure, rapport and ‘collusion’ in qualitative interviews. Women’s Studies International Forum 2017 61, 81-86.

Office for National Statistics. (2011). Poverty, and Social Exclusion in the UK and EU, 2005-2011. The National Archives website, last accessed 6 Dec 2021.

Suri H. (2011). Purposeful sampling in qualitative research synthesis. Qualitative Research Journal 2011 11(2), 63-75.

Van Bergen APL, Wolf JRLM, Badou M. et al (2019). The association between social exclusion or inclusion and health in EU and OECD countries: a systematic review. European Journal of Public Health 29(3), 575-582.

Photo credits

- Photo by Gregory DALLEAU on Unsplash

A sense of belonging is essential to well-being, and to be excluded can be life-limiting. How hard do people have to fight against gutter-press stereotyping of those seen to be on the fringes merely to sell newspapers?